The defence policy (Strong, Secure, Engaged) is dead, long live the defence policy! As of April 8, 2024, and following two years of anticipation, the defence policy update (DPU) is out. Titled Our North, Strong and Free: A Renewed Vision for Canada’s Defence, this document shifts Canada’s defence priorities to the North and commits $73.3 billion worth of investments over 20 years (on an accrual basis).

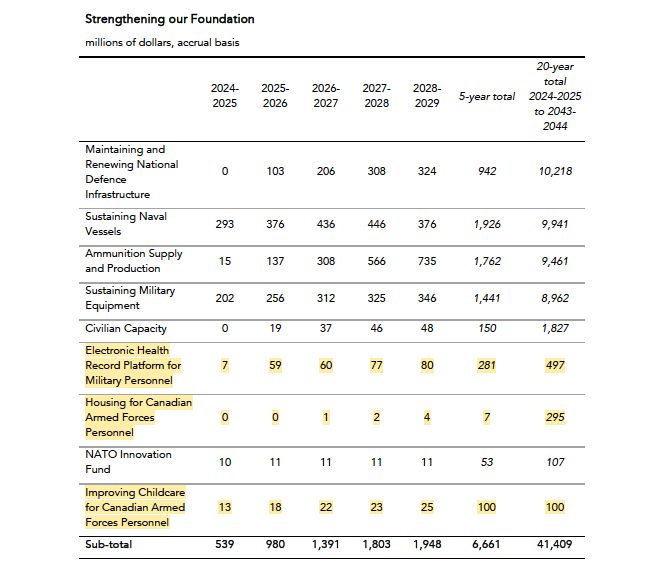

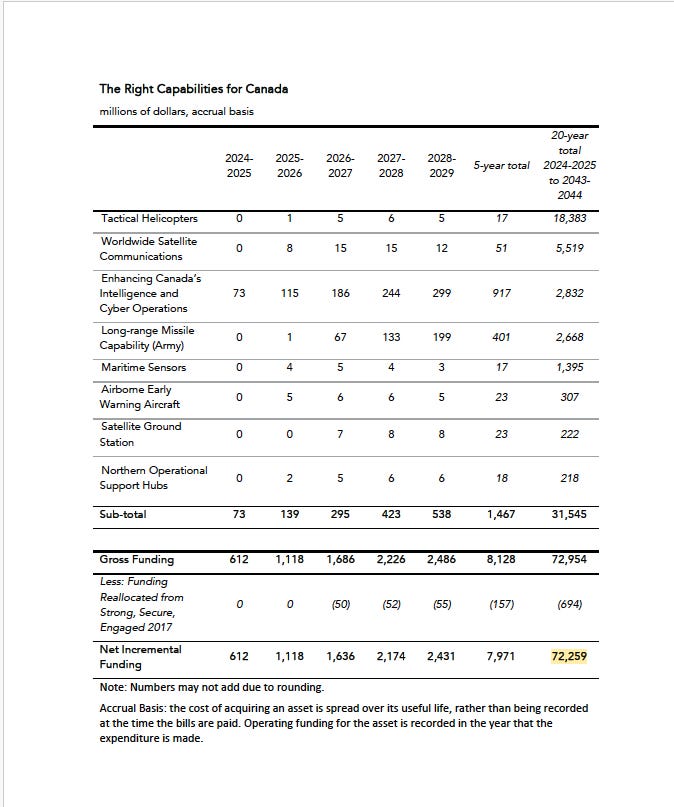

The investments are massive – and I recommend you listen to the money and procurement experts,1 you will not get a breakdown of the spending here beyond those two tables.

Here, I want to focus on personnel and how it fits within the larger defence policy. From my perspective, the personnel piece is quite light. Given the context in which the CAF finds itself (personnel shortage and Reconstitution), the optimist in me was hoping for a doubling down of the personnel commitments made in Strong, Secure, Engaged.

What we find ourselves with, however, is a set of disjointed commitments for recruitment and retention-related measures, not all of which are funded. Additionally, there is no connection between the personnel situation and the ability of the Canadian Armed Forces and the Department of National Defence to deliver on the DPU commitments. It was all the more disappointing given the consultation I took part in, and the Minister’s foreword to the document.

Let’s start from the begin…

Overview – Our North, Strong and Free (#ONSAF for the initiated)

In principle, the DPU does not stray away from Strong, Secure, Engaged. The document reaffirms that the Defence Team objectives are to be “strong at home,” “secure in North America,” and “engaged in the world.” To do so, the DPU commits the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces to eight core missions:

Detect, deter and defend against threats to or attacks on Canada;

Detect, deter and defend against threats to or attacks on North America in partnership with the United States, including through NORAD;

Lead and/ or contribute forces to NATO and coalition efforts to deter and defeat adversaries, including terrorists, to support global stability;

Lead and/ or contribute forces to international peace operations and stabilization missions with the United Nations, NATO and other multilateral partners;

Engage in capacity building to support the security of other nations and their ability to contribute to security abroad;

Provide assistance to civil authorities and law enforcement, including counter-terrorism, in support of national security and the security of Canadians abroad;

Provide assistance to civil authorities and non-governmental partners in responding to international and domestic disasters or major emergencies; and

Conduct search and rescue operations.

The Strategic Environment

The DPU is unequivocal in naming Canada’s security challenges and its adversaries (Russia & China). More specifically, it lists the following concerns:

Climate change and Its destabilizing impact on our Arctic and North

Challenges to the International Order

Strategic competition (In the Euro-Atlantic and the Indo-Pacific).

Instability around the world (Iran, threats in the cyberspace)

The changing character of conflict

Note that while those categories are listed as separate, a lot of them overlap. They aim to present a holistic view of the threat and strategic environment.

The Vision

The new policy has two objectives: (1) “strengthen the foundations of our military;” and (2) “deter and defeat new and emerging threats.”

A recurring theme within the document outlines how connected these two are: “our insurance against instability and geopolitical uncertainty is a ready, resilient and relevant Canadian Armed Forces capable of defending Canada, ensuring security in North America, and contributing to an international order that is free and open, inclusive, stable, and government by the rule of law.”

To do so, the Defence Team commits to:

“Asserting Canadian sovereignty”

“Defending North America”

“Advancing Canada’s Global Interests and Values”

“[Adopting] A Strategic Approach to National Security”

There has been a good commentary on the strategic ambitions and of ONSAF, as well as the spending outlined in it – here are a couple:

Dr. Rob Hubert on CBC’s “The Current”: https://www.cbc.ca/listen/live-radio/1-63-the-current/clip/16055188-protecting-arctic-sovereignty

Dr. David Perry with CBC’s Linda Ward: https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1.7168352

Dr. Philippe Lagassé & Dr. David Perry in The Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-canadas-new-defence-policy-commits-to-exploring-instead-of-committing/

Alexander Rudolph on cyber: https://canadiancyber.substack.com/p/canada-is-creating-a-cyber-command2

To some’s frustration, I will not discuss any of the capability purchases or the exploration of acquisition. I do note that the commitment to build a Cyber Command and the integration of emerging technologies is significant to the military’s personnel management and generation.

However, there is a lot more to discuss on the personnel front, an aspect of the policy that has been under-discussed so far.

Personnel & #ONSAF

In terms of rhetoric, the personnel challenge is front and centre in ONSAF. In the early pages, the document acknowledged that a lot more to do in terms of retention (expressing the goal of “revers[ing] an unsustainable trend of attrition”), the importance of personnel in the implementation of the defence policy and the defence of Canada (“none of this work is possible without our people”), and the objective to built a “ready, resilient, and relevant” military includes mention of personnel.

In the vision statement, ONSAF even reads:

We will be guided by the overall objective of ensuring our military has the people, equipment, training and infrastructure needed to detect, deter and defeat threats in, over, and approaching Canada–– in the air, on land, on and under the sea, and in space and cyberspace.

Two of those elements (“people” and “training”) relate to personnel management and generation.

However, out of four pages directly engaging with personnel, there is about one page worth of initiatives.

So let’s break this all down.

1. Culture Change

Although this section does not open Chapter IV of ONSAF, it is the first concrete and extensive one. And while the first paragraph underlines the commitment to combat “all forms of misconduct and unprofessional behaviour in our organization,” the section reads as a political document rather than a policy one.

It is a section that takes stock of the work done so far, by:

Listing the reviews that contribute to culture change/ addressing misconduct (the Arbour Report, the Fish report, the report of the Advisory Panel on Systemic Racism and Discrimination, and the National Apology Advisory Committee report);

The publication of a new ethos, Trusted to Serve;

Changes in the selection process of general and flag officers (with the introduction of a character-based leadership assessment);

The implementation of the Declaration of Victims’ Rights and the creation of a Victim's Liaison Officer program

The adoption of “a trauma-informed approach to workplace reintegration for respondents;”

The establishment of “an expanded Restorative Service program;”

Improvement in the delivery of relevant training;

The creation of the Positive Space program

The introduction of Bill C-66 (see previous stackies for more on that)

The setting up of the External Monitor (CDL editorial: as recommended by Mme Arbour).

I do believe it is important to sit and take a moment to acknowledge the work the Defence Team and the Minister of National Defence’s office have done since 2021. Whether it is bearing fruit is a different question, but initiatives are being implemented.

2. Recruitment

This section recognizes that there is a shortage that has become “unsustainable.” To overcome such a situation, the Defence Team aims to:

“modernize its recruitment processes,” with an emphasis on leveraging “digital technology to improve applicant experience, speeding up required screenings, and connecting with new pools of applicants,” as well as modernizing training.

“create a probationary period to enable the faster enrolment of applicant,” “streamline the security clearance process,” “re-evaluate medical requirements, and abolish outdated criteria wherever possible to support efforts to urgently fill our personnel gap while also diversifying our forces.”

Those are in line with the Reconstitution Directive of 2022. Here, we see that the military is trying to continue expanding its recruitment pool and respond to the challenges that has come with it (the difficulty of processing application in a timely fashion, leading to attrition).

3. Retention

Retention is the personnel section with the most initiatives. Understanding the critical nature of retaining members when trying to recruit a shortage away, the military aims to:

“[R]eform how we manage military personnel, granting members increased career control and flexibility while enhancing performance management and succession planning.”

This includes “upgraded administrative processes and improved service delivery that is enabled by digital tools.”

“[E]xamine adjustments to personnel policies related to compensation and benefits, human resources policies, leave, and other supports for work-life balance for those in uniforms.”

“[E]stablish a Canadian Armed Forces Housing Strategy, rehabilitate existing housing and build new housing so that our military members can afford to live where they and their families are posted.”

[A]ccelerate the development of an electronic health record platform that improves the continuity of care in mental and physical health services for the diverse needs of members as they move between provinces and territories.”

[I]nvest in additional supports for military families, including by investing in affordable childcare.”

4. Strengthening the Canadian Armed Forces…

This is a 2-paragraph short section, that invites fast reading. However, in my view, this is the most impactful one. The second sentence of the first paragraph reads:

Through 2032, the Canadian Armed Forces will focus on building back to its authorized force size of 71, 500 Regular Force and 30,000 Primary Reserve Force members, and lay the foundation for future growth.

This is should give us pause. The goal of reaching 100,500 authorized trained effective strength dates back to 2017; the military expects to meet this number in 8 years from now. For some of my friends, their now young kids would be teenagers by then. I would be in my late thirties. It has serious implications on the implementation of the policy and on the defence of Canada – but more on that later.

The second paragraph presents a vision for the force structure when that personnel objective is met:

For every member deployed on an operation in Canada or abroad, another member is on high-readiness training preparing to relieve a colleague, and another member is returning from operations, adjusting to the transition and preparing to support others. This three-to-one deployment rotation is, in turn, supported by a robust structure of civilian and military specialists that enable every operation, such as logistics officers, intelligence and IT specialists, military police, and legal advisors, trainers, health services, HR, finance, and other forms of administrative support.

CDL’s 2 cents™️ There is something to be said here about the tooth-to-tail ratio (but it is a Monday night before the federal budget and we will have to put a pin in it).

5. … and Civilian Capacity

That one is short and sweet, and easy to understand:

Defence will increase the number of civilian specialists employed in priority areas that are essential to the future growth and development of the Canadian Armed Forces. A larger civilian workforce will increase our capacity to recruit and train new soldiers, service our capabilities, purchase new equipment, increase our stocks of ammunition, accelerate digital transformation and upgrade infrastructure. They will also fill critical gaps in functions that are essential to carrying out our operations today and into the future, such as staffing, security screening, and information technology. (emphasis in original).

Even though this could become a fraught objective when a change of government occurs (see Mr. Poilièvre’s comments on defence spending and his stance on the size of the federal civilian bureaucracy), I believe this is a smart move. In a personnel crisis where middle career members leave in substantial numbers, seeing where the military could feel the gap with civilians of similar experience and expertise could be extremely valuable. The policy commits over $1 billion over 20 years on an accrual basis for this endeavour, $150 million of which will occur over the next five years. For now, we do not know what this will look like and how this will be pursued.

That sounds quite extensive. So what’s the problem?

When it comes to prioritizing a critical shortage of personnel in a pressing security and defence context, it is very much “damned if you do, damned if you don’t.” If the defence policy focused on the personnel crisis, we would hear many arguments about the government not taking the security environment seriously enough.

And yet…

Given the policy took 25 months to come out, and the state of military personnel (16,000 short, from the latest numbers mentioned), I would have expected to see more. It did not necessarily have to outline each and every initiatives put in place (although the list of capabilities being acquired or “explored” is quite precise, in contrast). However, it would have been useful to see how:

ONSAF connects to the Reconstitution Directive and the Retention Strategy, and the progress done.

the funded initiatives align with data on attrition.

ONSAF seeks to advance the progress of the Strong, Secure, Engaged personnel-related lines of effort.

the goal of reaching trained authorized strength by 2032 is feasible and the data that supports it.

Would have that made ONSAF a much longer document? Yes. Could it have been difficult to negotiate such an annex in a document that is inherently political? Absolutely. However, it is hard to read the personnel section of ONSAF and think that the personnel file continues to sit outside the larger strategic considerations and threat environment.

When dealing with such a strategic document, it would have been interesting to see it all personnel related issues and challenges are connected with the vision and the larger objectives of the policy (for a concrete example: how do you expect the CAF to build an effective cyber command quickly given the recruitment and retention issues?). All the acquisitions, missions, as well as digital transformation will have a significant impact on the workload of present and future troops. Being deliberate and explicit in terms of the changes in the force structure, personnel management, and the difficulties of balancing all of those with members’ wants and needs would have sent a stronger message.

The problem exists in the discussions related to what we understand as culture change.3 While the military and defence civilian have a moral obligation to ensure that misconduct is reduced as much as possible and that, should it occur, is managed the best possible way, it is often forgetting the strategic obligations of doing so: (1) preventing misconduct is preventing what the military calls “unwanted retention;” (2) misconduct can destroy trust and morale in a unit, which can in turn hinder mission success.

Additionally, as of today, it does not seem that there is a clear, cohesive plan on how to go ahead and implement the policy within the context of a personnel shortage. I know this is a complex affair– I am not pretending I know better than anyone else. Retention and attrition in a heightened threat environment is no easy feat. Yet, the policy could have given us more; even though it is an inherently political document that took a lot of negotiation.

But to end on a positive note, however, let me echo the words of RAdm (ret’d) Jeff Hamilton in the latest episode of Defence Deconstructed: the CAF can get it done – it has shown the capacity to do so in the past. Maybe in slower ways than we would like, but they get it done.

And maybe this time, the devil that is in the detail is actually a benefactor.

It is cheesy, but being cautiously optimistic can be quite nice.

David Perry, Philippe Lagassé, Craig Stone, Ross Fetterly to name a few.

I do take note of the lack of women being interviewed on the defence policy update. I have thoughts on that.

For more on that, read my rant: https://www.cgai.ca/culture_change_beyond_misconduct_addressing_systemic_barriers

Training for culture change is less effective than.selecting for it. Changing assessment tools is more politicized and difficult. I suggest caf recruit for multicultural personality then throw in IQ, education and conscientiousness. And physical fitness and courage and initiative.