My colleague at Canadian Cyber in Context, Alex Rudolph, joked to me last summer that it was “hot personnel summer.” As we are sitting here in late January 2025, I think we can say that fiscal year 2024-25 is turning out to be The Year in Personnel.™️

This week was particularly monumental: changes to medical requirements for entry are soon coming to place, and Steven Chase published a story on the state of recruitment and retention. Also add a new Reconstitution Directive that came out in the Fall.

We see movement – definitely in the right direction. But as the incorrigible Debbie Downer that I am, I am concerned that we are still missing some critical points of data that could help us overcome the personnel crisis on our end.

Where are we?

As of December 2024, the CAF is 94,005 people strong (64,461 Regular Force and 29, 544 Reserves). This means that the military is 7, 495 members short (Regular Force and Reserves combined).

This is great news. The CAF is growing and closing in on its personnel gap and saw an increase of slightly under 2,000 members since July of 2023.

The numbers outlined above are for the total strength – not the total effective strength (TES, i.e., the number of members that are ‘functionally operational”). The TES is 52,510 people. To note, the CAF interprets the total authorized force of 101,500 troops as outlined in Strong, Secure, Engaged as the “total strength.” So we cannot really compare that target to the current TES. But it is some good information in terms of how that translates into readiness.

So, overall, things are good.

But (you saw this coming) there are some reasons to pause and be concerned. At this stage, each “occupation authority” (Navy, Army, Air Force, Chief Military Personnel) fills on average 66% of its target intake, with the RCAF having the highest intake at 73% and the Army the lowest at 63%.

And despite the prioritized processing for priority occupations, the CAF is currently meeting on average 30% of its targeted intake (with Maritime Technicians [MARTECH] being the occupation with the lowest achieved intake at 27%). Fully understanding the MARTECH challenge has been a long standing one, it simply shows how much it matters to drill down. on those numbers. In fact, the 2016 Office of the Auditor General report I keep on citing noted that the CAF was continuously unable to meet targets for occupations experiencing a shortage:

I cannot say that the problem is exactly the same; there hasn’t been a study of recruitment and retention since that report, despite Strong, Secure, Engaged establishing the target of 101,500 military personnel in 2017. But the same fault line seems to emerge.

To further put all of this in context, let’s talk about the strategic intake plan (SIP). In short, it is the total number of people the CAF would like to recruit to keep a certain level of readiness. Between fiscal year 2017-18 and fiscal year 2019-20, the “unfilled SIP” was between 14% and 18%. During the pandemic, for obvious reasons the unfilled SIP reached 61% – but since, the CAF has not gone back to previous levels of intake. In 2021-22, the unmet SIP was 23%, but it climbed to 37% in 2022-23, to now overing at 34%.

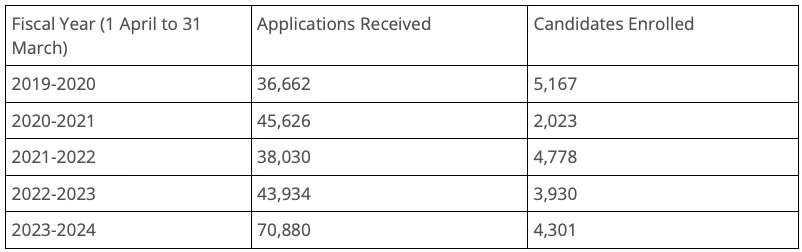

Something is amiss here, and it is clear that it is an intake issue. In 2023-24, close to 71,000 people applied to join the CAF, less than 4,500 made it in.

This year to date, the CAF has received 53,640 applications and enrolled 4,280 applicants. Since the opening of the CAF to permanent residents in November 2022, 149, 992 people applied and 10, 275 made it to the CAF. We are at a less than 10% enrolment rate, and there is no public qualitative data to suggest a cause for such a low admission rate.

A note on permanent residents: Since 2022, 39,830 permanent residents applied to join the military. Only 263 enrolled. The CAF has been quite open about the challenges that come with processing applications from non-Canadian citizens (for clearance-related reasons), so not much of a surprise there. But if the CAF was desperate to expand its recruiting pool to ensure such a policy move would help with the personnel shortage, it is disappointing to see such a gap between expectations and results. Recently, the Chief of the Defence Staff also said there are changes made to clearance requirements to accommodate for pace of application processing.

This leads us to the…

Changes of medical standards

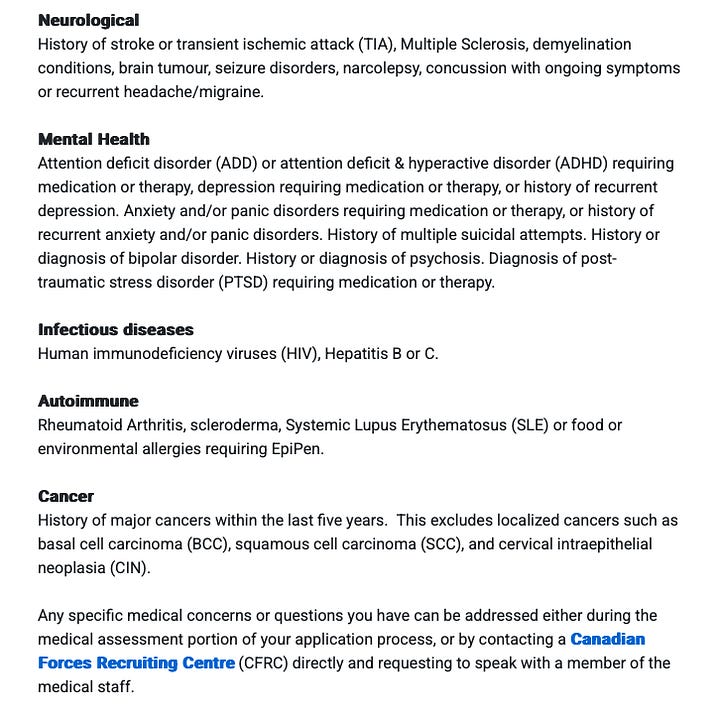

In an interview with The Canadian Press, Gen. Carignan announced that the CAF has loosened medical barriers to entry in the CAF. Mentioned ailments included hyperactivity, ADHD, asthma, allergies, and anxiety. The Chief of the Defence Staff said that medical issues will be assessed on a case by case basis. The policy/ change has not been made public, and it seems like it has yet to be communicated widely to the CAF.

I cannot even begin to half speculate as to what the policy and its implementation looks like. At a surface level, and to show my bias, I do think it is a good idea and I have not been shy in saying as much.

But as always, the devil is in the details. My main concern revolves around whether or not the proper policies and structures have been put in place for this new approach to recruitment to have the intended effects. As a Chief Petty Officer 1st Class told me a month or so ago, people who are diagnosed with anxiety, ADHD, and other ailments can receive accommodations and continue to serve within the CAF – there are some tensions with the principle of “universality of service,” but it is something that the CAF has managed. Now, I would need to see what the policy looks like: what are the risks the CAF is accepting? What is the threshold for acceptance within the CAF? What occupations are barred?

This last question is in fact the most important in my view. If I were an applicant, I would like to know what trade/ occupation are open to me based on my medical issues. I looked up the forces.ca website, and it requires one to dig a bit to find the FAQ and get to the medical part of eligibility. This is what the website reads – as you can see, we do not have that much detail.

Additionally, I do not know if this page is older than the change in policy. I’ll try and research further (but if you have insights for me, feel free to respond to this stackie!).

Do I think this will tip the balance towards closing the personnel gap the CAF is experiencing? I do not know, but uncertainty is not enough to reject the idea altogether. I believe it makes sense for the CAF to be more flexible with medical standards based on occupation. Expanding the recruiting pool and not closing itself to talent for manageable medical issues is a good thing. And it is more an issue of having access to talent than numbers itself – last fiscal year, applications increased by over 1.5 times from the previous years. It is about making sure the CAF can access the full range of Canadians and permanent residents who want to serve and have the skills to do so.

What gives me pause in terms of outcomes is (1) the experience with permanent residents joining the CAF (see above) and (2) the implementation of the policy – not only in terms of recruitment, but what happens when those folks are serving and in need of institutional support.

The Reconstitution Directive

This one flew under the radar for many of us, and it took a CDS interview and healthy dose of sunk cost fallacy pushed me to finally sit down and read it.

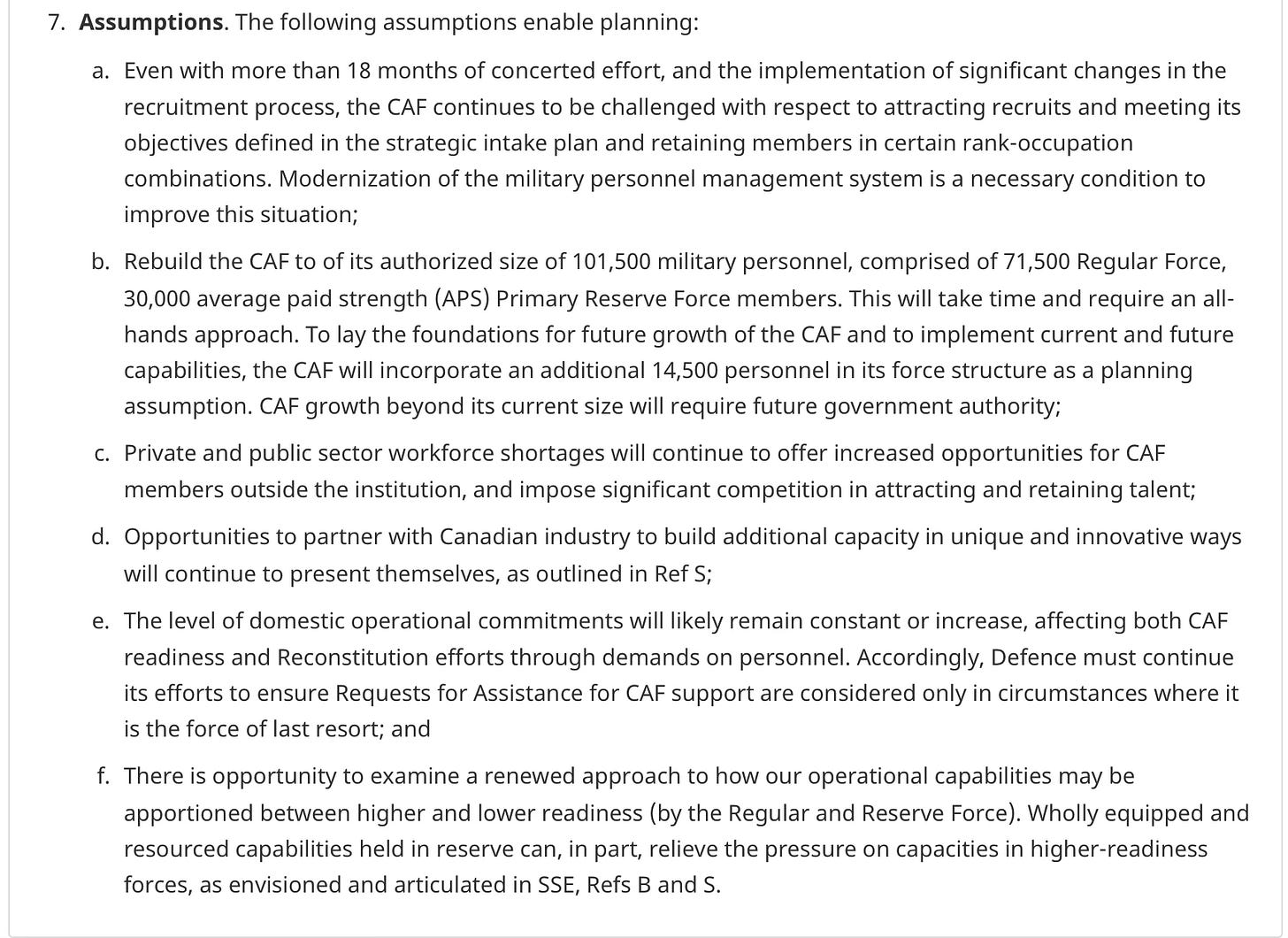

The second directive on CAF Reconstitution (let’s call it “Reconstitution II”) came out on October 31, 2024 and “builds on the work begun under” the September 2022 directive. The first directive identified two, concurrent phases, spanning from 2022 to 2030: Recover (2022-25) and Build (2022-2030). The second directive will continue pursuing these two themes.

Reconstitution II presents the personnel challenge as follows:

To address those challenges/ “assumptions,” the Chief of the Defence Staff and the Deputy Minister outline 10 themes that will guide Reconstitution lines of efforts:

Increase Personnel Generation by attracting and recruiting military personnel

Optimize Security Clearance Processing

Manage and Retain Military Personnel

Improve Military Personnel Digital Enterprise and Support

Increase, Optimize, and Retain Civilian HR

Operationalize New Vision for the Reserve Force

Enable recruitment and retention through improved Culture

Strategically recalibrate force employment levels and integrate strategic campaigning in line with the Defence mandate to align with the GC Priorities

Optimize the Institution including Force Structure to meet the needs of the Future Force and to remove obstacles to advance Reconstitution

Leverage Digital Transformation and Data-Driven Processes to maximize Reconstitution efforts.

For the CAF to meet its objectives within each teams, the Chief of the Defence Staff and the Deputy Minister welcome risks and want the various authorities to: be innovative and creative; push decisions to the lowest appropriate level of authority; maximize retention of personnel with needed expertise; optimize operational tempo; reassess the rate of OUTCAN postings, and reduce collective training activities.

Through Reconstitution II, the Chief of the Defence Staff and the Deputy Minister both commit that the military will be 101,500 people strong (as directed by Strong, Secure, Engaged) by 2030. This is two years earlier than expected in Our North, Strong and Free (and we’ll take it).

Reconstitution II does not change the wheel (GOOD!) and appears like an update and recommitment to the concept and the associated efforts in an Our North, Strong and Free era.

Note: You can see that there is an assumption the CAF will be given room to increase by 14,500 once it has met its Strong, Secured, Engaged total authorized force target. This is quite speculative on the CAF’s part, as this needs to be approved by Cabinet, and we do not know who will be in government by then. For more one this, read Steven Chase’s article: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-canadian-military-ready-to-deploy-at-border-if-needed-top-soldier/ . But let me reiterate: this additional 14, 500 is not a given and needs to be approved by Cabinet to become reality.

Attrition

In that same Canadian Press interview mentioned above, Gen. Carignan stated that “the CAF’s rate of attrition is “very healthy” at about eight or nine per cent.”

I do not agree with that statement, which has not made me many friends on Twitter (gosh it feels juvenile to even type this). I expressed myself poorly, and it is better for me to explain myself here.

This metric is both used in comparison with other allies (who happen to have on par or higher rates of attrition, such as Australia, New Zealand, and the UK) and civilians sectors (whose attrition ranges from 4.7% in the public sector to 10.2% in the private sector – pre-pandemic).1 The rate is not contextualized with overall intake year to year.

In fact, the Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis data I am citing projects that the CAF will lose about 5,531 people by the end of fiscal year 2024-25. It is anticipating to have a total intake of 7,155 by the end of that same year. This means that the CAF could be able to increase by 1,624 troops by March 31, 2025.

However, the CAF has only enrolled 4, 280 people by December 2024. Will it be able to enrol 2,875 people (i.e., double and then some what it has been able to enrol over the past nine months) over the next three months? That remains to be seen.

In short, the context in which the attrition occurs matters. Obviously, something would be extremely wrong if a military had 10% and over attrition, even if it was able to replace those people.

Why?

Because it is expensive (in terms of money, time, and knowledge) to lose a service member, and high attrition rates can reveal cultural and institutional issues (should they be studied qualitatively). In the CAF, you cannot just hire someone to be a Master Warrant Officer/ Chief Petty Officer 2nd Class when one leaves. DAOD 5031-1 “Canadian Forces Military Equivalencies Program” outlines the feasibility of finding CAF equivalencies for non-CAF experience, but this will not remove challenges with institutional memories.

That being said, I wonder if this DAOD leveraged to advertise a trades-related career in the CAF (thinking of MARTECH, specifically).

To double down (and expand a bit), attrition rates need to really be studied in the larger personnel context. Considerations need to include: (1) as outlined earlier: intake – can the CAF replace the loss in terms of members? And (2) context, i.e., is the institution experiencing a shortage? how is this attrition impacting readiness?

To add in terms of context, I do not find the most useful to look at attrition globally, as it does not reveal the critical conditions in which certain occupations find themselves (yes, I am referencing MARTECH as an example). So yes, the overall attrition rate in the CAF could be considered healthy, but it is not across the board. And if priority occupations/ occupations in critical shortfall experience high levels of attrition and low levels of intake, then looking at CAF-wide attrition is not the most useful metric.

That’s it, folks!

To anticipate the Debbie Downer criticism: (1) I know – I am French and that’s what I do; (2) I do not think we can fully positive spin this issue. This is not to say that all is bad – we are seeing progress. But I am not one to declare the war is won when the prospects of winning battle is looking pretty decent and that we can improve in order to increase our chances to win.

Using numbers from Irina Goldenberg and Nancy Otis, “Canadian Armed Forces Reconstitution: The Critical Role of Personnel Retention,” 30-31, in Canadian Defence Policy in Theory and Practice, vol. 2, eds. Thomas Juneau and Philippe Lagassé (Cham: Pagrave Macmillan, 2023). Note that this chapter uses some data from before the pandemic.